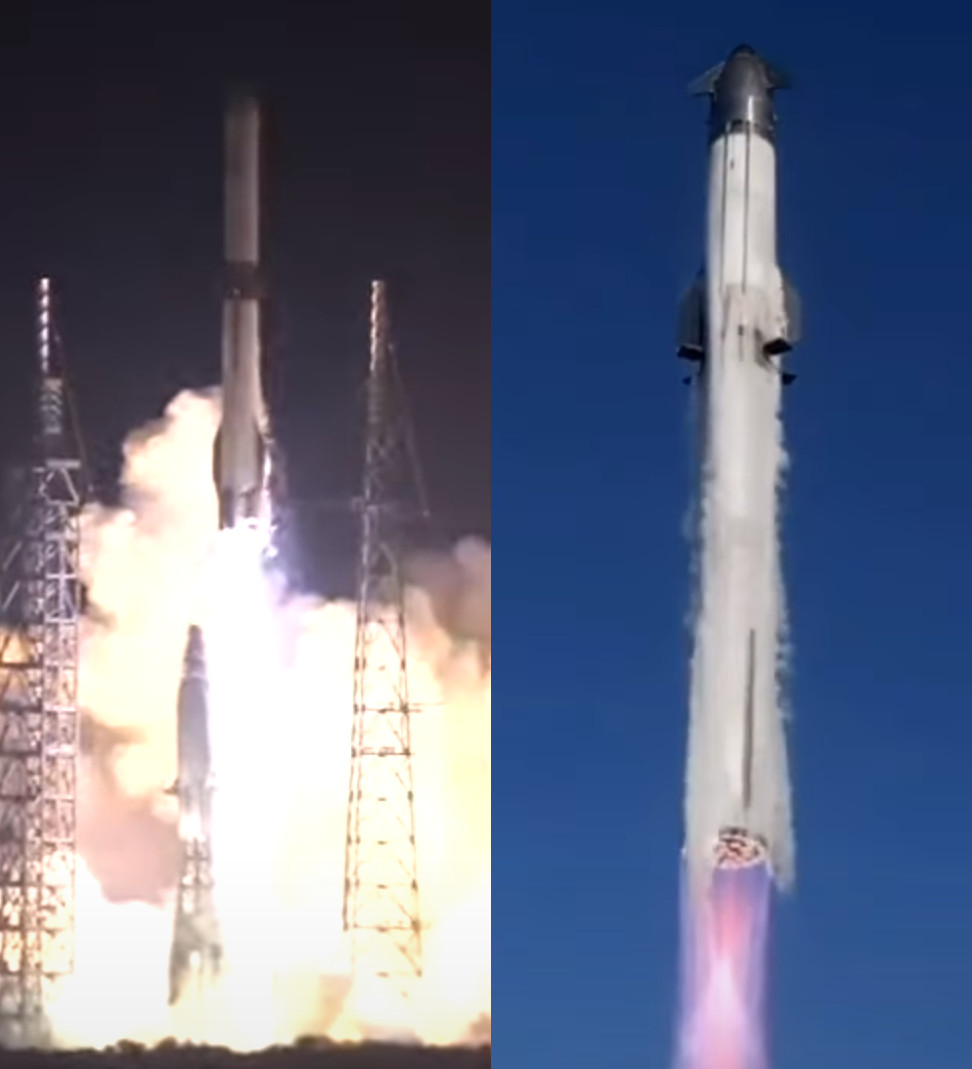

January 16 2025 saw two test launches of large launch vehicles: The first flight of Blue Origin’s New Glenn, and the seventh flight of SpaceX’s Starship.

New Glenn flight 1

This was the first orbital flight attempt by Blue Origin, the first flight of the New Glenn rocket. Blue Origin made the leap from a successful very small, suborbital, rocket, New Shepard, straight into a heavy lift orbital launcher, New Glenn.

Announced in 2015, New Glenn went through a long and careful development period, mostly under wraps, finally getting to the launchpad in December 2024. On its first flight, carrying a Blue Ring prototype (Blue Origin’s satellite bus currently under development), both stages performed perfectly during ascent, successfully placing the payload in Medium Earth Orbit. All 7 BE-4 methane-burning engines in the first stage ran perfectly during ascent, just as in the 2 flights of ULA’s Vulcan rocket, which also has a first stage powered by Blue Origin’s BE-4 engines. The second stage demonstrated for the first time the hydrogen-burning BE-3U engines, derived from the BE-3 engines that have successfully carried New Shepard in 27 flights. This included demonstrating engine startup at zero g (something which cannot be tested on the ground), both after separation from the first stage, and a relight in orbit (a very different thermal environment, on engines that have already been stressed out during the first burn), used to raise the payload from a low to a medium orbit. This demonstrated all the critical capabilities of the rocket for its contracted payloads, including NASA’s ESCAPADE mission to Mars, due to launch in the spring of 2025, and the uses for the Space Force’s NSSL program.

The only part of the New Glenn flight that did not succeed was the landing of the first stage. This very bold attempt for a first flight was always a secondary objective, and Blue Origin was always cautious to inform it was a very risky and uncertain attempt, which would be a great bonus if it worked, but not a critical mission objective. This was expressed in the naming of this first stage: “So You’re Telling Me There’s a Chance“. For the customers, it is irrelevant what happens to the launcher after it delivers its payload to the intended orbit: reusability only has relevance to the operator, in case it may enable them to save costs for the next launch (whether or not there are savings from reusability being always a very uncertain estimate).

New Glenn’s next launch is nominally expected for March 2025, carrying the first prototype of their Blue Moon lander, in a test flight to Lunar Orbit, in the development for delivering a Blue Moon vehicle to land astronauts on the Moon for NASA’s Artemis V mission in 2029.

More about New Glenn in our article.

Starship flight 7

Later on the same day, SpaceX performed their latest test flight of Starship, the seventh overall, the first one with the V2 version of Starship. The flight was planned to be suborbital, with the addition of dummy satellite payloads, to demonstrate ejecting them through the ship’s small payload bay doors.

Shortly after the first stage made its landing as intended, at T+7:39 the on-screen telemetry info showed the second stage’s engines shutting off, one by one, before the stage had reached the intended suborbital velocity. The on-screen telemetry and video were interrupted, followed by SpaceX announcing the second stage was lost. This was followed by airplane flights in the Caribbean, of the coast of Turks and Caicos, being directed to divert or placed on holding patterns to avoid falling debris:

Then, social media started showing a multitude of videos taken from the ground and on flights around Turks and Caicos, showing Starship had an explosion, then the fragments entering the atmosphere:

Just saw the @SpaceX launch from the Disney Treasure!!! @elonmusk @DisneyCruise pic.twitter.com/kkaDk4swBB

— evenstar7479 (@evenstar7479) January 16, 2025

Starship 7 debris over Turks and Caicos pic.twitter.com/EJ3CeMQdmQ

— Nick Pagliuca (@nickpags45) January 16, 2025

After the incident, SpaceX informed “Preliminary indications suggest an oxygen/fuel leak in the cavity above the ship engine firewall, which was substantial enough to build pressure beyond the venting capacity.”.

We now eagerly wait to see the next developments on both rockets’ path to enter operation.

More info

New Glenn 1 launch video:

Starship 7 launch video:

This post is also available in:

Português