New Glenn is in the pad, being prepared to make its first flight at 01:00 EST on January 16.

This will be the first orbital flight done by Blue Origin, who is making the leap from their successful, small, suborbital, fully reusable crewed rocket, New Shepard, directly into the domain of a heavy lift, reusable, orbital rocket. If this first test flight succeeds, this will be the world’s second largest operational rocket.

The launch will be streamed live on many platforms, including on Blue Origin’s website.

Update: see how the launch went in our article.

Blue Origin’s path to New Glenn

Blue Origin is the oldest of the current wave of space startups, being founded in 2000 – 2 years before SpaceX. As opposed to the usual practice for these startups, Blue Origin did not publicize its objectives or designs to seek external funding (investors, loans, government contracts), operating mostly silently, completely funded by its founder, Jeff Bezzos. Only by the time of the first, low-altitude, flights of their first technology prototype, called Goddard (named after the rocket propulsion pioneer, Robert Goddard), they released information on their plans for a commercially available vehicle, New Shepard, that was in development. New Shepard (named after the first American astronaut to reach space, Alan Shepard) is a small, suborbital, human-rated, completely reusable rocket, intended primarily to carry private client astronauts in suborbital flights. New Shepard achieved the distinction of being the first rocket to go to space and land propulsively, in its second attempt, in 2015 – ahead of SpaceX’s first successful landing of a Falcon 9 first stage. Only at the time New Shepard was presented, in 2015, did Blue Origin make public its plans for a much, much larger, orbital, vehicle, New Glenn (named after the first American astronaut to orbit the Earth, John Glenn). At the time of its announcement, it was projected to become the world’s largest operational launcher, but it was beat to that title by NASA’S SLS becoming operational in 2022.

New Glenn’s design

New Glenn has two stages. The first is reusable, landing propulsively on an autonomous barge in the ocean, and a landing will be attempted from the first flight. The first stage uses methane as fuel and liquid oxygen as oxidizer, powered by Blue Origin’s BE-4 engines. While New Glenn has never flown yet, the BE-4 series of engines has flown, completely successfully, in the Vulcan rocket. ULA contracted Blue Origin to provide the engines for Vulcan, becoming the first methane fueled engines to successfully propel an orbital flight. The second stage uses liquid hydrogen as fuel and liquid oxygen as oxidizer, propelled by Blue Origin’s BE-3U engines, a modified version of the engine that has carried New Shepard on 27 flights. Classified as a heavy-lift rocket due to its nominal 45 ton capacity to LEO (Low Earth Orbit), if successful, New Glenn will be the second largest operational rocket today, only after NASA’s SLS (nominally, with a 70 ton capacity to LEO in its block 1 version, up to 130 ton for block 2). Besides the mass capacity to LEO, New Glenn is notable for its size (98 m height, same as SLS, with a 7 m diameter), with the largest fairing of any current rocket. While Falcon Heavy has a higher nominal mass capacity to LEO (64 ton if none of the boosters is reusable, less than 50 ton if all first stage boosters are to be recovered), Falcon Heavy’s small fairing (3.7 m in diameter, 145 m3 in volume) severely limits its use for Earth orbiting payloads: it cannot fit enough payload to use its full mass capacity to LEO. Even for GTO (Geostationary Transfer Orbit), Falcon Heavy has never transported more than 6.5 ton to while recovering all first stage boosters, far less than New Glenn’s stated limit of 13 ton, and even Falcon Heavy’s stated 27 ton limit to when discarding the boosters. New Glenn, with its 7 m diameter fairing, has 458 m3 in volume, even allowing some larger payloads than what is advertised SpaceX’s Starship would have (around 1000 m3), due to Starship’s small opening to deploy its payloads, plus its internal trusses that intrude in the payload space.

Due to its size, transporting New Glenn from distant facilities would be slow and expensive, so Blue Origin built a new facility for its construction near launchpad SLC-36 at the Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, in Florida. The vehicle is integrated horizontally, then moved unfueled by Blue Origin’s purpose-built transporter to the pad, where it is attached to the erector, a structure that supports the rocket while it is lifted to vertical position at the pad. After the first stage lands, the landing barge goes to Port Canaveral. After being unloaded from the ship, the rocket only needs a short trip back to the nearby integration facility.

The flight of New Glenn’s first stage makes extensive use of the aerodynamic control solutions developed and tested for New Shepard, with dynamic stability for both forward (upward) and backward (for the flight down) phases ensured by different fin deployment attitudes. The large upper fins, besides providing stability, can provide significant lift, enabling farther travelling cross-range for landing without using propulsion. The custom designed landing barge is relatively small for the size of New Glenn, but is enabled by the landing being done while the barge in motion, so it can achieve active stabilization against waves. Also, the BE-4 engines are able to throttle down all the way to 40%, enough to allow New Glenn to hover, thus providing a softer and more precise touchdown, another legacy from New Shepard.

While Blue Origin keeps details of its future plans under wraps, it has been mentioned that: New Glenn would be their smallest orbital rocket; they worked on a project called Jarvis, to make a reusable second stage; there are possibilities of a third stage and larger fairings for New Glenn; Blue Origin’s primary goal is to make launches cheaper.

Scheduled New Glenn flights

- Blue Ring prototype. January 2025. First flight of New Glenn; first landing attempt; first orbital flight for Blue Origin. Blue Ring is the satellite platform (or bus) being developed by Blue Origin, which customers will be able to contract for their missions, providing them with a spacecraft with power, communications and navigation capabilities. Also the first NSSL demonstration – a qualification flight to enable New Glenn to fly payloads for the Space Force’s National Security Space Launch program.

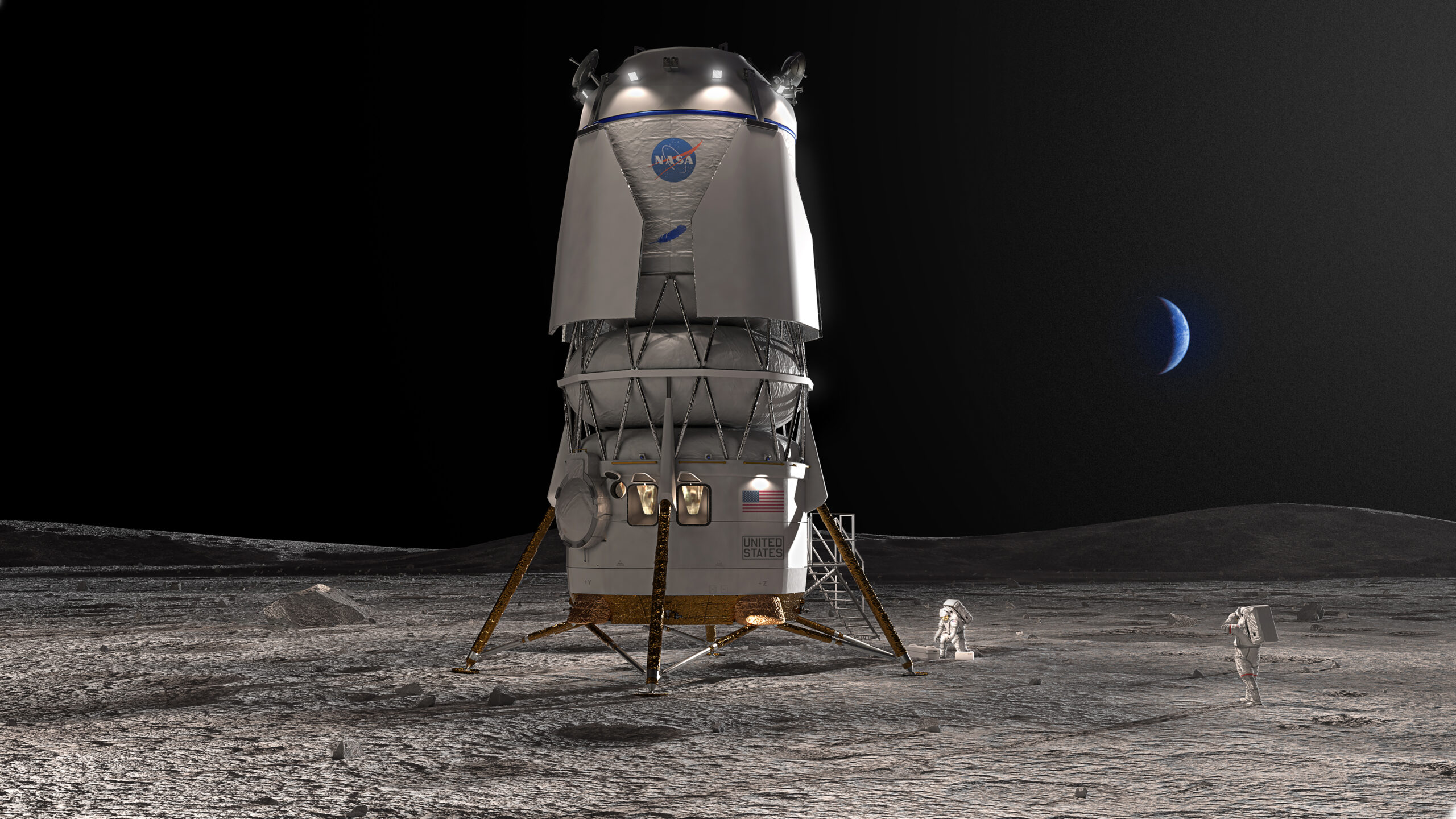

- Blue Moon Pathfinder 1. March 2025. Blue Origins’s first Blue Moon prototype flight to the Moon, in preparation to fulfill its HLS (Human Landing System) contract for a manned landing on the Moon for NASA’s Artemis V mission, in 2029. Also the second NSSL demonstration.

- ESCAPADE. Spring 2025. First contracted payload, for NASA’s ESCAPADE mission, sending two orbiters to study Mars’ outer atmosphere.

- KuiperSat. 2025. First flight of Project Kuiper’s satellites from a New Glenn. Kuiper is an Amazon subsidiary building a large LEO constellation for providing Internet access, and has flown its first prototypes on other launchers.

- Blue Moon Pathfinder 2. 2025.

This constitutes a solid and ambitious development plan, including sending ESCAPADE to Mars on the third flight. This was intended for New Glenn’s first flight, subsequently delayed to the third to avoid cost overruns from running many mission launch attempts. But it highlights that: 1) New Glenn’s development was deemed so thorough that it could carry out this contracted Mars mission on its first flight. This reflects Blue Origin’s development strategy of proceeding carefully, with lots of thorough simulations and tests before proceeding to flights only when at high confidence of success. 2) The rocket has so much available energy this Mars launch could be slipped to March 2025, well out of the minimum energy launch window for Mars (Oct-Nov/2024), without having to wait for the next window Nov-Dec/2026. 3) The price for the contract was remarkably low: $20 million. This can be contrasted to the $94 million NASA paid SpaceX for launching Sentinel 6 into a Low Earth Orbit (LEO), a payload that required so little energy from the launcher that the Falcon 9 was able to land back at the launch site, making it the cheapest possible operation for a Falcon 9.

This portfolio also includes sending Blue Moon prototypes to the Moon already in 2025, despite Blue Moon being awarded Artemis V only in 2023, for a landing in 2029. This would be the first flight of an Artemis HLS prototype. This can be compared to SpaceX’s HLS, which was contracted in 2020 for the Artemis III mission, with a first unmanned landing initially scheduled for early 2024 – and currently with no concrete estimate of when it will happen, due to the delays with Starship’s development.

Besides the missions listed above, New Glenn seems to have a solid market base, with contracts already in place for other commercial customers, including Project Kuiper (12 launches, with options for 15 more), OneWeb (5 launches), Eutelsat, mu Space Corp, SKY Perfect JSAT, Telesat and AST Space Mobile. Lots of those consist of heavy, multiple-satellite launches to geostationary orbits, a market segment with much fewer options and much higher prices than the abundant choices for LEO.

More info at

Tour of the Blue Origin factory where New Glenn was being built

Tour of the CCSFS facilities, including the launch tower

Our article on New Glenn’s first flight

This post is also available in:

Português